By Anadolu Agency

ISTANBUL

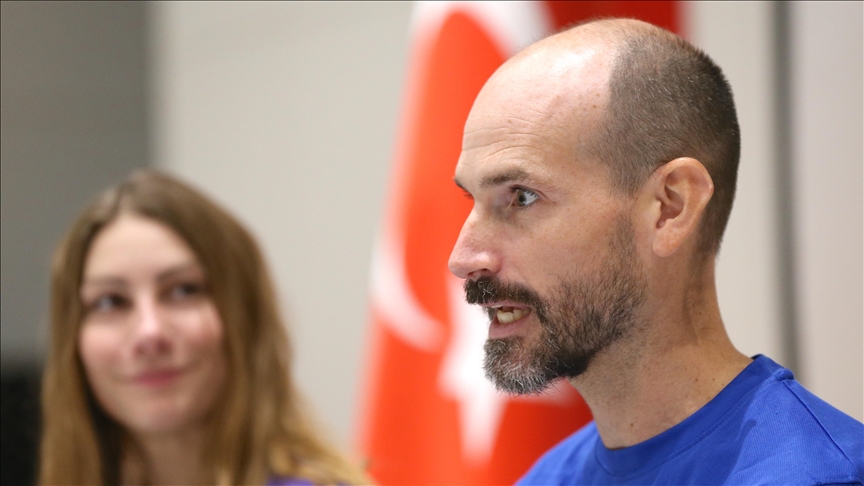

American explorer Mark Dickey’s visit to Türkiye was longer than he expected – and took a turn for the worst that he never saw coming.

He was part of a research group that headed into the Morca Cave, the third-deepest in Türkiye, located in the country’s southern Mersin province.

Their mission was to map the underground system of the cave, a labyrinth of constricted passages and plunging vertical tunnels, located in a remote area some 2,200 meters (7,217 feet) above sea level in the Taurus Mountains.

Dickey was about 1,040 meters (3,412 feet) inside the cave on Sept. 3 when he fell seriously ill, suffering sudden gastrointestinal bleeding.

What followed was what rescuers have since described as one of the most challenging cave rescue missions ever done. At least 200 rescuers from several countries worked for days and finally managed to get Dickey out a little after midnight of Sept. 11.

“Logically, I was like, I’m probably going to die,” Dickey told Anadolu in a video interview from his hospital room in Mersin, hours before he was discharged.

He had lost a lot of blood by the time the first rescuers reached him with medication and blood bags for a transfusion. That left him too frail to move on his own, flitting between bouts of consciousness.

“I really have no way of describing it … just a whole host of symptoms hit me all at once,” he said.

“It was a pretty wild ride. Feeling loss of consciousness, that you have to throw up, that you have to go to the bathroom, that you’re getting hot flashes, cold flashes, that you’re tired, lethargic. All of these things kind of hitting you all simultaneously.”

Dickey’s experience in a career as a rescuer and caver proved critical in his survival. He has been a cave rescue trainer for over a decade and has a background in the fire service.

He knew that no matter the distress, he had to move and make it to a team member.

“You have to take the right actions at the right time. Right then, the necessary action was not to stop moving. So whether it’s hard or not, I finished climbing my way up to Jessica,” he said, referring to his fiancee and fellow expedition member Jessica Van Ord.

She was the one who then made the climb out of the cave to alert authorities.

“I started telling her what I was feeling, what the symptoms were, and based on that, she would be able to take action. Even if I was unconscious, she would at least have an idea of what was going on,” he explained.

Fear of the unknown

Dickey is no stranger to caves and has been through his share of challenges over his career.

But this was something he had never experienced or even imagined.

“This was a totally unknown medical problem. 100% unknown. So that’s what makes that so scary in itself,” he said.

“If you fall and break a leg, you know you fell and you broke a leg. If you have a rock fall on your head, you know a rock fell on you. But an internal medical problem that you can’t see – that’s scary.”

With his life on the line, all of Dickey’s training and survival instincts kicked in hard. He knew there was no room for emotions and that rational thinking was his key to survival.

“Emotions are going to cause you to make poor decisions. It was very rational logic. What are my signs? What are my symptoms? What’s happening? What decisions have to be made? What plans have to be made?” he said.

Conflicting thoughts raced through his mind, from thinking that there was no risk to his life to fearing the absolute worst.

“It went like ‘I don’t think this is a life risk.’ ‘I’m pretty sure I’m okay.’ Rest. Get out of the cave myself,” he said.

“Then it transitioned into, ‘Oh crap, this is a life risk. I need help. This is serious.’ Then it became ‘I’m probably going to die, but I’ll do my best not to.’”

Over time, it became “harder and harder to talk,” said Dickey.

“It was getting hard to count my pulse on my wrist. I was very close to going into shock. And mentally I knew that and I was maximizing my chance for success. But logically, I was like, I’m probably going to die.”

The 41-year-old caver was trapped for almost 10 days as rescue teams charted a way to ease him toward the surface.

Rescuers did get him medicines and other essentials during that time, but he could not eat or drink throughout.

“In the process of receiving the medications and the medical help … every single day that went by, I’m not eating. I’m not drinking. So … I had 10 sequential days of no food whatsoever,” he said.

“They did start providing some IV-based nutrition, but IV nutrition is a very significant caloric deficit. So my body started consuming its own fat, its own muscles. It started consuming itself to generate energy … On top of that, my stomach was at risk at all times … So you had to be very, very careful … You didn’t want it to rupture.”

‘Turkish government’s rapid response is what saved my life’

For Dickey, it is clear that he owes his life to the authorities and brave volunteers who put themselves on the line for him.

That gratitude was clear to see on his face as he described the moment he first made it out.

“That felt amazing. I popped up and there are all these people waiting for me, and a lot of them I knew,” he said.

“It wasn’t just like, here’s all these strangers, all these random rescuers, all these random people that had saved me. A huge amount of these people were friends. Huge amount of these people are like part of the caver family … The entire rescue, that was family saving me. That felt good.”

The Turkish government’s role was ‘insanely critical,” he said.

“When Jessica got out of that cave, contacted the Turkish government and said we need medical supplies, she got them and she got them in time to save my life,” he continued.

“The Turkish government’s rapid response is what saved my life, period.”

Despite his brush with death, Dickey’s spirit of adventure is as strong as ever and he is raring to get back into the field. More important for him at the moment, though, is for people to understand that “this was a fluke medical issue.”

“This is not representative of the dangers of caves or caving. Caving is actually one of the safer sports out there,” he emphasized.

“There are international expeditions going on every single year in countless locations. Rescues are exceptionally rare.”

We use cookies on our website to give you a better experience, improve performance, and for analytics. For more information, please see our Cookie Policy By clicking “Accept” you agree to our use of cookies.

Read More